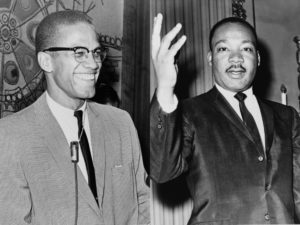

T’Challa and Killmonger have been compared to Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. This is an unsurprising lens to view the relationship between black leaders given their distinctive philosophies and hold on the popular imagination. The idea is that both have noble goals, but that while one goes about his in a gracious, loving way, the other is a violent radical.

But I’m convinced this analogy is not particularly helpful for two reasons. First, it reduces them into caricatures bearing little resemblance to who they were in real life. Today, Dr. King has a national holiday and is a revered figure. But “gracious” and “loving” were not terms often used to describe him during the Civil Rights movement. Gallup never showed him with more than a 45% favorable rating in his lifetime. In fact, by 1966, 63% of Americans viewed him unfavorably. He was apt to be called a demagogue and a Communist. He died leading a poor people’s campaign that could get him accused of class warfare.

This shouldn’t be surprising. He was unpopular to so many precisely because he challenged so many popular attitudes about black people. In his own way, he was a radical. He admitted as much himself. The purpose of his demonstrations in Birmingham, he wrote in a famous letter from its jail, was “to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue [of racism].” He had no patience for self-described moderates. In fact, he had “almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.”

Malcolm X is usually remembered as an angry racist. And understandably so. He referred to whites as “white devils.” He argued that blacks should not identify with America because it was a “white man’s country,” and asserted that identifying as Americans was akin to “the ex-slave who is now trying to get himself integrated into the slave master’s house.” When a white college girl asked how she could help, he turned her away.

There was more to the story. In 1964, he went on his obligatory once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage to Mecca. What happened there changed his views. He had “eaten from the same plate, drank from the same glass, slept on the same bed or rug, while praying to the same God…fellow Muslims whose skin was the whitest of white, whose eyes were the bluest of blue, and whose hair was the blondest of blond…” He went onto say that this “was the first time in my life that I didn’t see them as ‘white men.’” So before he died, Malcolm X had renounced the views that comparisons to him draw upon.

If we really wanted to compare Killmonger and T’Challa to Malcolm X and Dr. King, we would need to compare them to Malcolm X and Dr. King as they actually were, not necessarily as we now remember them.

Second, even if we caricature the two, I don’t see how either Killmonger or T’Challa resembles them. If we insist on remembering Dr. King only as a kindhearted man who preached love, then neither Killmonger nor T’Challa fits the bill. Killmonger for obvious reasons; he’s a murderer who’s willing to cause a civil war and use Wakanda’s military to cause destruction around the world. T’Challa for his part might not be violent, but he certainly doesn’t advocate universal love. He says nothing when a man argues for excluding refugees from Wakanda because they bring problems. And for most of the movie, he refuses to use Wakanda’s knowledge to improve the lot of nearby countries, or the rest of the world. You wouldn’t say he dreams that Wakandans will be able to sit down with citizens from other countries at the table of brotherhood.

Neither resembles Malcolm X. Killmonger might seem like he does because of his violence and hatred. But there are important differences. Malcolm X’s religious beliefs were core to who he was. We have no indication that Killmonger has any. Where Malcolm X was eventually able to question his hatred and move past it, Killmonger never does. And while T’Challa doesn’t appear to care about anyone else but his own people, he never harbors the resentment that continues to characterize how people see Malcolm X.

So I don’t see Malcolm X or Dr. King as a useful analogy in this movie. I will say, though, that Killmonger calls to mind another important 20th century black leader: Marcus Garvey. Founder of the United Negro Improvement Association, Garvey wanted to see blacks unite, become self-sufficient, and ultimately go back to Africa and found an independent nation. Killmonger wants Wakanda to become that nation.

To advance his vision, Garvey met with Ku Klux Klan leader Edward Clark; he thought he could work with the KKK because both organizations advocated racial purity. Killmonger worked as a CIA operative for a country he regarded as an imperialist oppressor of blacks to gain the knowledge and skills he would ultimately use to take over Wakanda. Both men were willing to work with whites they detested to further their causes.

Garvey’s ideology lived on after he died. Killmonger is his heir.